Nuoruuden arvostamisesta – mitä elämää nähnyt runoilija-miljonääri kirjoitti kahdeksan vuotta ennen kuolemaansa?

Seikkailuni elämäkertojen ja ihmisten mietteiden lukemisen suhteen jatkuu. Luin jonkin aikaa sitten runoilija-yrittäjä Felix Dennisin kirjan How to Get Rich, jonka hän kirjoitti kahdeksan viikon aikana kahdeksan vuotta ennen kuolemaansa. Dennis kuoli 67 vuoden iässä maaliskuussa 2014. Dennissin tarina on mielenkiintoinen: hän syntyi köyhiin olosuhteisiin, koulut jäivät kesken ja Denniss ryhtyi yrittäjäksi – Denniss halusi rikastua.

Dennis kirjoitti kirjoja ystävänsä kanssa (kirjat Muhammed Alista ja Bruce Leestä) ja perusti oman kustantamoimperiuminsa, joka kustansi muun muassa tietokonelehtiä. Parhaiten Dennis tunnetaan ehkäpä lanseeraamastaan miestenlehdestä Maximista. Myöhemmällä iällä Dennis perusti hyväntekeväisyyssäätiön, joka keskittyy puiden istuttamiseen Britanniassa. Vuosiensa aikana Dennis lahjoitti suuria summia hyväntekeväisyyteen, ja myös käytti paljon rahaa prostituoituihin ja viineihin.

Kirjassaan How to Get Rich Dennnis kertoo seikkailuistaan ja niiden jättämistä henkisistä arvista sekä siitä mitä vaaditaan rikastumiseen. Dennis myös kertoo runoudesta ja siitä miten hän runouden löydettyään alkoi käyttää kolme tuntia päivässä omien runojen kirjoittamiseen.

”Does it all matter [writing poetry]? Three years ago a woman came up to me after a poetry reading. She was crying softly. As I signed her book, she kept saying: ‘How could you know? How could you know? You are not a mother. How could you know?’ She squeezed my shoulder as her husband led her away into the night. So, yes. It bloody well does matter– to me and to her, at least.”

–ote Felix Dennissin nettisivuilta

Felix Dennis (kuvalähde: http://api.theweek.com/sites/default/files/legacygeneric/Felix_3_ChrisHarris.jpg)

Erityisesti minut kuitenkin Dennisin kirjassa pysäytti noin 1500 sanan kohta, jossa Dennis koskettavasti pohtii omaa elettyä elämäänsä ja kaikkea sitä aikaa, jonka hän käytti rikkauksien haalimiseen. Dennis puhuu katkelmassa siitä miten hän voisi vaihtaa kaiken satojen miljoonien puntien omaisuutensa, kaiken mitä hän on ikinä ansainnut ja kaiken mitä hän tulee ikinä ansaitsemaan, voidakseen olla jälleen nuori. Dennis kirjoittaa siitä, miten nuoruus on korvaamattoman arvokasta aikaa.

Olen kopioinut alle tämän englanninkielisen 1500 sanan katkelman alle suoraan Dennissin kirjasta How to Get Rich [Dennis, F,:, 2006, 250-254] ja toivoin, että saat katkelman lukemalla uudenlaista perspektiiviä elämääsi. Tämän postauksen kuvat eivät ole Dennisin kirjasta. Lisää Dennisistä voit miehen kotisivuilta.

”

The Quest for Wealth: A Health Warning

There is no fortress so strong that money cannot take it.

–Cicero, In Verrem

Cicero was a subtle man. Money can reduce any fortress; but which fortress is he speaking of, do you think? The enemy’s (whoever the ”enemy” may be) or your own? Let us assume it is the latter. So what is your fortress? It is your inner core, your integrity, your belief in the worth of others and the love of those dear to you. Not to mention your own worth. It arises from belief in yourself. And, dor a few, from a belief in their own destiny.

Excessive idolatry of money will ”take” all those. It will corrode both self-belief and love. It will stretch integrity on the rack. It will ”take” the fortress; and it will not be a pretty sight. Seeking substantial wealth is almost always a fool’s game. The statistics show that very few people ever succeed. Most of them should never have made the attempt in the first place. They aren’t suited to it, and if that sounds defeatist, then consider the fact that the search will take up a great deal of your waking life for many, many years.

You cannot get rich without ”wasting” that time. Not unless you were born lucky – so lucky that luck has squatted on your shoulder virtually from birth. You would not need to get rich, then. You would be rich, in one way or another. Time is finite. Which is a fancy way of saying that you only have so much of it – then it will run out. When you are young, time seems to stretch into the distance for so far that surely it will always be on your side? When the young catch the old unawares, they may sometimes glimpse a look of naked envy, which is then instantly disguised.

And the old have reason to be envious. Truly, truly, they do it. Ask me what I will give you if you could wave a magic wand and give me my youth back. The answer would be everything I own and everything I will ever own. In The Odyssey we read:

And Achilles replied, ”Do not speak soothingly to me of death, glorious Odysseus. I would rather live on earth as a bondsman to the meanest peasant, than be king of the shadows.”

Homer, as always, is right. If you are young and reading this then I ask you to remember just this: you are richer than anyone older than you, and far richer than those who are much older. What you choose to do with the time that stretches out before you is entirely a matter for you. But do not say you started the journey poor. If you are young, you are infinitely richer than I can ever be again.

Money is never owned. It is only in your custody for a while. Time is always running on, and the young have more of it in their pocket than the richest man or woman alive. That is not sentimentality speaking. That is sober fact. And yet you wish to waste your youth in the getting of money? Really? Think hard, my young cub, think hard and think long before you embark on such a quest. The time spent attempting to acquire wealth will mount up and cannot be reclaimed, whether you succeed or whether you fail.

Even should you succeed in becoming rich, unlikely as that is, what will you have achieved? Independence of a kind? The luxury to choose what you wish to do with the rest of your life? Happiness? No, no and no. You will not achieve any of those things. Not when you have too much money. As Francis Bacon, one of the greatest minds ever to grace England’s corridors of power, warned in his Essays:

I cannot call riches better then baggage [hindrance] of virtue. The Roman word is better, impedimenta. For as the baggage is to an army, so riches to virtue. It cannot be spared of left behind, but in hindereth the march; yea, and the care of it someone loseth or disturbeth the victory.” It does indeed. Wealth makes many demands and, by the time you have acquired it, you will be prey to certain habits.

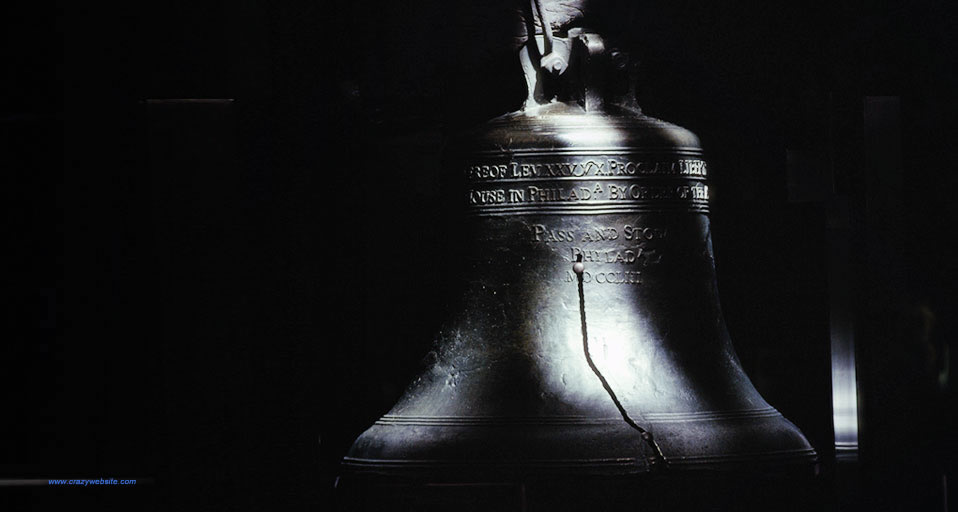

You will fear to lose it and must spend a great deal more time to defend it. No on is ”independent” of the human race. ”No man is an island entire of itself, every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Heed the words of John Donne, finest of poets: ”And therefore never send to know for who the bell tolls: it tolls for thee.” Aye, so it does.

No luxury of choises for rich little you. You will be too busy keeping the sea from washing away the sand you have spent so long collecting at such terrible cost to your health and your sanity and your relationships with others. It is always thus. There is no escape. You believe (I know you do) that it will be different for you. But it won’t be. It never is.

Happiness? Do not make me laugh. The rich are not happy. I have yet to meet a single really rich happy man or woman – and I have met many rich people. The demands from others to share their wealth become so tiresome, and so insistent, they nearly always decide they must insulate themselves. Insulation breeds paranoia and arrogance. And loneliness. And rage that you have only so many years left to enjoy rolling in the sand you have piled up.

The only people self-made rich can trust are those who knew them before they became wealthy. For many newly rich people, the worlds becomes smaller, less generous and darker place. It sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it? Ridiculous and gloomy. But then, you are to consider that I have been very poor and I am now very rich. I am an optimist by nature. And I have the ability to write poetry and create the forest I am busy planting.

Am I happy? No. Or, at least, only occasionally, when I am walking in the woods alone, or deeply ensconced in composing a difficult piece of verse, or sitting quietly with old friends over a bottle of wine. Or feeding a stray cat.

I could all those things without wealth. So why do I not give it all away? Because I worked too hard for it. Because I am tainted by it. Because I am afraid to. All those reasons and more. Perhaps, if I am lucky enough to become old, I will accumulate something else: the courage to give it away before I die. That would be a good thing, I think. (When I die, it is all going to a charity called ”The Forest of Dennis.” You see, even when I do a good thing with money, my ego insists that I name it for myself. Not a good sign.”)

Giving money away when you are dead takes no guts. No courage. But to divest yourself of hundreds of millions of dollars, or the greater part of your fortune, before your death? That would be something to be proud of, don’t you think? It even makes logical sense. For what is left afterward but a few years by a graveside and years of bickering and waste over a complex will? (The wills of the rich are always complex.)

Bitter years, where lawyers count the number of fairies they believe you once thought danced upon the head of a pin – years in which they enrich themselves at you descendants’ expense. A fine legacy, to be sure. But you must make your own choice. I have said my piece and I meant every word of it. This small part of my book was composed in my mind years ago. It was easy to write. I knew all of it before my fingertips touched my keyboard. It has troubled me for years and I thank you for allowing me to share it.

I suspect it will have little effect on you, though. You are probably young and tired of being poor. And tired, from the years of growing up and schooling, of being lectured. Very well. Let us return to a recap of the ”important bits” to help you on your journey [of getting rich]. But just before we do, can I ask you to do me small favor? Please lodge one fact in your memory: that the last one thousand five hundred words was an ”important bit”. In my hearts of hearts, I know it was the most important bit you will read in this book

Mark it with a bookmark and write today’s date upon it. Come back to it in twenty or thirty years, when new books printed on paper will be rare objects. Then cast your mind back to a time when you were young, and you first read this book, and to the thoughts of a fool, a rich poet, long dead, who once typed these words sitting in one of the most beautiful houses on earth, staring at a turquoise sea, sipping a glass of slightly chilled Chateau d’Yquem.

That will be enough for me.